Ethiopia is stepping up preparations to go ahead with a planned closure of a camp for Eritrean refugees, despite concerns among residents and calls by aid agencies to halt their relocation over coronavirus fears.

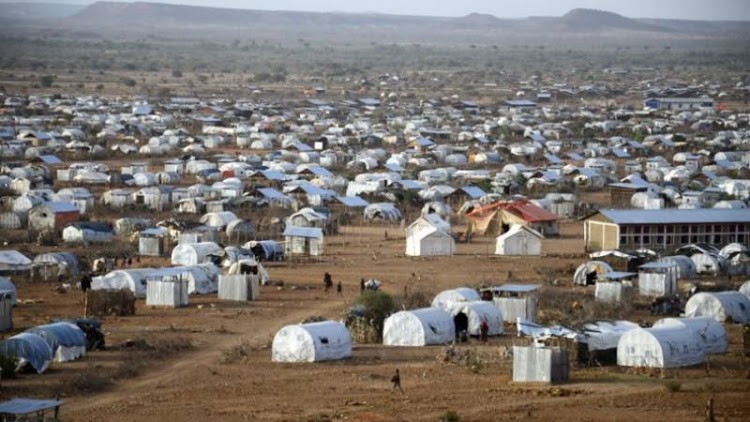

Home to some 26,000 people, including some 1,600 minors, Hitsats is one of four camps in the northern Tigray region hosting nearly 100,000 Eritrean refugees, according to the United Nations refugee agency (UNHCR).

Earlier this month, Ethiopia’s Agency for Refugee and Returnee Affairs (ARRA) announced to residents in Hitsats camp that the federal government had decided to relocate them to Mai Aini and Adi Harush camps, or offer them the possibility to live in towns.

The plan has yet to be executed amid the coronavirus pandemic, but officials say preparations continue.

“We are ready to start the relocation at any time,” Eyob Awoke, deputy director general of ARRA, told Al Jazeera, noting that the declaration of a state of emergency last week due to the pandemic had forced authorities “to timely adapt the initial plan”.

“External factors are hampering us,” Eyob added, “but we can start with small numbers”.

“Hitsats refugees are suffering a lot from shortage of water, shelter and access to electricity,” Eyob said. “Merging of these camps is mainly required to ensure efficient and effective use of available resources.”

COVID-19 risk

The timeline and measures for the closure have not been shared with the UNHCR and other partners.

Yet, there are concerns that Mai Aini and Adi Harush camps are almost full and lack the infrastructure needed to cope with new arrivals, including sub-standard access to water.

In a statement sent to Al Jazeera on Friday, the UNHCR urged the government to put on hold any relocation effort, saying it risked making refugees vulnerable to COVID-19, the highly infectious respiratory disease caused by the new coronavirus.

“Any large-scale movement now will expose the refugees to risk of COVID-19 outbreak in camps”, the agency said.

ARRA assured that the transfer of the refugees would be carried out in a coordinated way. As of April 19, Ethiopia had 108 confirmed coronavirus cases, including three deaths.

In a letter sent to the UN at the end of March, refugees in Hitsats camp had also expressed deep concern about the prospect of the camp’s closure.

“We are in a deep fear, psychological stress and we need protection”, read the letter, which was seen by Al Jazeera.

“We feel threatened. They told us that if we decide to stay, we will lose any kind of support,” a refugee living in Hitsats camp told Al Jazeera.

Currently, only critical humanitarian and life-saving activities are running at the camp, as well as awareness-raising activities to prevent the spread of COVID-19. At the beginning of the month, the UNHCR and the World Food Programme reported that residents in Hitsats received a food ration for April.

Eritrean refugees are also allowed to live outside camps, but many do not want to leave Hitsats.

Other refugees eventually settle in the capital, Addis Ababa, but struggle to make a living and are highly dependent on external aid.

So far this year, ARRA has issued 5,000 official permits for refugees to live outside camps, according to the UNHCR, mainly for Eritreans in Hitsats and other camps in Tigray.

“In light of the current rush to close the camp, one is compelled to ponder whether the decision is more political as opposed to an operational one?” said Mehari Taddele Maru, a professor at the European University Institute.

The UNHCR, in its statement to Al Jazeera, said it could not speculate about the government’s rationale for closing the camp.

In a letter dated April 9, 2020 that was seen by Al Jazeera, ARRA communicated to all humanitarian partners that new arrivals from neighbouring Eritrea would no longer be offered “prima facie” refugee status, revisiting a longstanding policy of automatically granting all Eritrean asylum seekers the right to stay.

“We will have to narrow down the criteria for accepting Eritrean asylum claims, they have to demonstrate a personal fear of persecution based on political or religious action or association or military position”, Eyob said.

“Today, the situation is not like before, many people are coming to Ethiopia and going back to Eritrea.”

Ethiopian Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed sparked an historic rapprochement with Eritrea soon after taking office in April 2018, restoring ties that had been frozen since a 1998-2000 border war. His efforts in ending two decades of hostilities were cited by the Norwegian Nobel Committee as one of the main reasons for awarding Abiy the Nobel Peace Prize last year.

The rapprochement, however, has yet to lead to the full normalisation of the two neighbours’ ties, while activists’ hopes that the peace process would lead to major policy reforms within Eritrea have been largely dashed. The long-criticised universal conscription is still in place while crippling restrictions on press freedom and freedom of expression continue.

“We cannot return to Eritrea”, a refugee in Hitsats told Al Jazeera.

“For Eritreans, fleeing is one of the only real options to escape their government’s repression”, Laetitia Bader, a senior researcher for Human Rights Watch, said.

“Any policy shifts are definitely a risk to Eritreans’ right to asylum,” Bader said.

SOURCE: AL JAZEERA NEWS